The Visionary Sanctuary of Atotonilco – Mexico Pilgrimages

Something Sacred is Living in the Waters of Atotonilco

A chapel built to honor Jesus of Nazareth when looked at further becomes a macabre window into the mystic and perhaps psychotic visions of its creator, Luis Felipe Neri Alfaro.

I. BAJIO CALLING

Its easy to get romantic when visiting the Mexican heartland known as El Bajio. This diverse macroregion stretches from north Mexico City westward to the east edges of Guadalaraja. Contained within its town are extraordinary examples of new-world baroque architecture juxtaposing a deep legacy of creativity and independence.

In the shadows of the architectural masterworks like the Teatro Juarez in Guanajuato and the Aqueducts of Queretaro, exists a strong lineage of outsider artists who heard the clarion call to migrate to central Mexico and live out their creative vision among its many Pueblo Magicos.

– After the war, Surrealist Edward James left Europe to spend his middle ages in central Mexico’s jungles constructing the massive surrealist sculpture garden “Las Pozas”.

– The soviet film master Sergei Eisenstein was brought here to film in 1930 only to lose himself so deeply in the lifestyle that he never completed the movie.

– American WWII veteran Stirling Dickerson founded an Art School in an old tannery in San Miguel de Allende. El Instituto Allende was one of the only schools in Mexico that accepted USA GI Bill grants, causing an influx of eccentric veterans that helped turn San Miguel de Allende into an artist enclave full of good taste, good food and LGB-friendly neighborhoods.

…Oh, and Diego Rivera was born and raised in Guanajuato. His childhood home has been turned into a museum for his early work.

II. Pueblos Magicos

There are dozens of towns, small and large throughout El Bajio, and in between them are hundreds of fascinating sites with their own strange stories to tell. Here we find Mesoamerican structures like the Pyramids of Cañada de la Virgen, ruins of Spanish Conquest like the abandoned mining town of Mineral de Pozas, and hundreds of awe-inspiring Baroque structures protected through the official Pueblo Magicos designation. A sort of architectural Unesco instituted by the Mexican government to increase tourism and preservation within the country. Since launching the program with 32 towns in 2001, the count is now up to 132 towns and villages. Of the original 32, twenty four were located in El Bajio.

Today, we are 11 kilometers northeast of San Miguel De Allende exploring the Sanctuary of Atotonilco. A church of extraordinary historical significance, built in 1740 that manages to inhabit several eras of el Bajio. The unique history of the sanctuary ties the nomadic tribes of the Chichichimecas to the ecclesiastic empire building of New Spain, Mexican Independence, the 20th-century muralist movement, and perhaps even the post-war pilgrimages of modern visionaries.

The Sistine Chapel of Mexico

If the 250-year-old Sanctuary complex has made it onto your radar, it was most likely referenced as the “Sistine Chapel of Mexico” and it may be easy to assume it is just another magnificent edifice of violent Spanish conquest.

However, the Sanctuary of Atotonilco was primarily the vision of a single, intensely pious priest from Mexico City.

Father Luis Felipe Neri de Alfaro was born into New Spanish nobility only to eschew all earthly desires including food, pleasure, and even basic comfort. Obsessed with violent traditions of penance through physical pain, Alfaro would spend his life in elective suffering while using his vast inheritance to complete a quest transmitted to him by Jesus Christ in a mystic vision.

Obsessed with violent traditions of penance through physical pain, Alfaro would spend his life in elective suffering while using his vast inheritance to complete a quest transmitted to him by Jesus Christ in a psychedelic vision.

Bringing his vision into existence, Alfaro supervised as nearly every surface of the Sanctuary was covered in fresco paintings depicting the life of Christ. These frescos, most of which were composed and completed by self-taught local painter Antonio Marinez de Pocasangre, represent a particularly violent rendering of the Christ story.

The Sanctuary itself was built on sacred grounds near thermal hot springs where the Chichimecas would perform fertility and purification rituals deemed “pagan” by Father Alfaro.

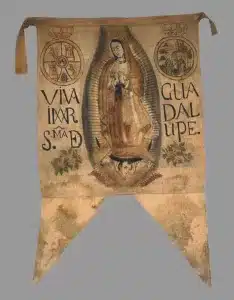

The complex would also forever change the small town’s role in the history of Mexico. It was here in 1810, that the newly formed rebel army took refuge from the initial battles of the Mexican War of Independence. During their stay, they created their famous banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe, based on a painting inside the sanctuary. (left) Furthermore, the preservation of this church is a source of pride for Mexicans, as it is where Ignacio Allende’s marriage to Agustina De las Fuentes (who later died shortly after) took place.

III. The Vision of Father Neri de Alfaro

“…Dreams and daydreams are a terribly important source of nourishment for the nervous system; they have a decisive influence on the actions of the awakened.” – Diego Rivera

Father Luis Felipe Neri de Alfaro was extreme by any standard, yet, much of his violent penances are still practiced today by church members in Atotonilco. The majority can be linked back to the methods Alfaro employed while establishing the Sanctuary. “Realistic” reenactments of the crucifixion and the stations of the cross still occur yearly.

Father Luis Felipe Neri de Alfaro was extreme by any standard, yet, much of his violent penances are still practiced today by church members in Atotonilco. The majority can be linked back to the methods Alfaro employed while establishing the Sanctuary. “Realistic” reenactments of the crucifixion and the stations of the cross still occur yearly.

Alfaro believed strongly in practicing corporal punishment and bodily cleansing as a part of his religious observance. He regularly flagellated himself, wore a self-made thorns-encrusted vest, and walked about in sandals with internally installed spikes. As mortifying as those were, the one that imprinted heavily in my imagination were a pair of silver knee guards he had forged that separated his kneecaps at the joint as he walked.

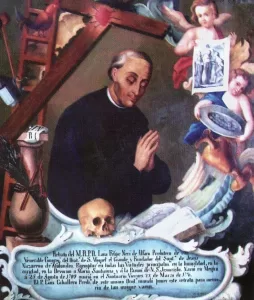

Father Alfaro slept in a coffin and received a variety of self-requested punishments daily until his death in 1776. According to some church historians, Alfaro died at 6 AM Atotonilco time, which is 3 PM Jerusalem time, the same hour Jesus was believed to have passed. Father Alfaro’s body is buried in a tomb in a wall near the main altar with a painted epitaph next to it. (above)

Little is known of Alfaro’s pre-seminary life. He was born in Mexico City into a Creolle family of recognized nobility, his mother and father had gained the honorifics of Don and Doña (Don Esteban Valero de Alfaro and Doña María Velázquez de Castilla). A title rarely bestowed to those born in “New Spain”.

His mother raised him as an ascetic and practiced continuous sacrifices both Earthly and spiritually throughout his childhood.

After attending seminary and receiving his bachelor’s in Theology and Philosophy, Alfaro was primed to reap the rewards of colonial nepotisms. Instead, he eschewed his birthright of fortune and chose to dedicate his life to the priesthood at the newly founded Templo del Oratorio de San Felipe Neri in San Miguel el Grande. (San Miguel de Allende today) A place where the secular post-reformation teachings of Father Philip Neri were being put into practice. The Oratoria had moved into the building in San Miguel and begun reconstructing the property in 1710.

Whilst passionate and intense by today’s standards, the main focus of the Oratorians was that of post-reformation communal outreach, Eucharistic unions, and the mystical experience. Nothing in Oratorian culture suggests the violent forms of penance Alfaro would obsess over during his career overseeing the construction of the Atononilco Sanctuary.

After completing his studies at the Oratoria, Alfaro was sent to oversee the expansion of a church in Dolores, 44km northeast of San Miguel el Grande. It was here, in the late 1730’s where Father Alfaro began to take ill. There is no information as to what had stricken him, just that he lived in a perpetual state of physical discomfort and chronic nausea.

The Vision

Alfaro had heard of the healing thermal waters that flowed from a small river in the settlement of Atotonilco. He arranged to stop and stay at the tiny Inn “the Hacienda de Atotonilco” near the hot springs on the way back to San Miguel. (“Atotonilco” means “Place of Hot Waters” in the traditional local language of Nahuatl. )

It was here, in the early months of 1740, Alfaro would have his visionary experience. After finding intense relief within the thermal waters, Alfaro wandered back towards the Hacienda when he stopped and found comfort under a nearby mesquite tree, eventually falling into a deep sleep.

At sunset, he would experience a waking dream of such intensity, it would influence the rest of his life. Jesus of Nazareth appeared to Alfaro, crowned with bloody thorns, carrying the crucifix. Christ pointed to the mesquite tree Alfaro was sleeping under and instructed him to construct a sanctuary for penance and prayer.

Throughout His Life, When Recounting The Vision, Alfaro Made Sure To Always Put Penance First.

In his writings, Alfaro frequently eludes to Antotonilco appearing similar to the holy lands of Jerusalem, with its yellow high desert sunsets and sparsely vegetated lands. The acacia trees found in the town are today considered the scholarly choice for the “burning bush” from which Moses divined a vision from God.

Using permission from the church and family money, Alfaro set to work building his Sanctuary. Buying the Hacienda Atotonilco and the land around it, including all 26 exit points of the thermal springs, which he incorporated in the plumbing of the original design.

On May 3, 1740, a ceremony was held where Father Alfaro blessed the first stone laid to construct El Santuario de Jesús Nazareno en Atotonilco. The Sanctuary of Jesus of Nazareth in Atotonilco.

IV. THE HIGH DESERT OASIS OF ATOTONILCO

Atotonilco is a high desert landscape sparsely smattered with acacia shrubs and mesquite trees near the little Riveria Laja. For centuries, this area of the Laja has been a pilgrimage site not only for Catholics but for the native populations as well, all seeking the healing waters of the thermal springs.

My wife and I are here primarily to spend a few days soaking in the waters to relax my chronic back spasms. The warm waters made the pre-sanctuary site a destination for Chichimeca pilgrimages. Chichimecas is an old term taken by the Conquistadors to describe the nomadic tribes that inhabited El Bajio. To the Spanish the word meant “barbarians” but the original translation of the word Chichimecas refers to the tribes of the “land of milk”, aka el Bajio. Father Alfaro himself acknowledged these traditional “pagan” ceremonies, using them as moral fodder for his case to build the church.

“The barbarous Indians did make use of this place in heathen times as a center for their idolatries. . . . This has been a place of lawlessness and sensuality. Under the pretext of assembling for the medicinal baths, there have been contests, music, feasts, games, and sinful practices induced by these disorderly gatherings.” – Father Alfaro Neri 1740

When constructing the Sanctuary, Father Alfaro focused on snuffing out what remained of the pagan ceremonies while maintaining the pilgrimages the Chichimecas took to Atotonilco. He did this by supplanting the ancient bloodletting ceremonies of fertility with bloodletting penances in the name of Christ, puncturing themselves with maguey thorns and washing away the blood of their wounds, i.e. their sins, in the thermal springs.

The evolution of these pilgrimages from “pagan” ceremonies to intense Catholic purification rites continues into the modern day where locals perform penance rites, puncturing themselves with maguey thorns crowns that can be bought from hawker stalls a block away from the Sanctuary.

Since its founding, the sanctuary has been one of the principal places in Mexico to practice the spiritual exercises of Ignatius of Loyola. which includes mortification of the flesh through flagellation and fasting starting two weeks prior to Easter Sunday, or to Spanish Catholics, Passion Sunday.

Today, in addition to the Ignatius of Loyola, the church body of Atotonilco also reenacts the full crucifixion, down to the minute.

On Good Friday, Alfaro would wear his spiked slippers and concaved knee plates and carry a heavy piece of wood down the main streets of Antotonilco with a crown of thorns piercing his head till his face was covered in blood.

When he reached the town square, a “fat” man he had paid began to beat him to the ground three times like Christ, then dragging him by his feet back toward the church, so the friction of the thorns would cause a trail of blood down the single dusty road of Atotonilco all the way to the Sanctuary.

He practiced mortifying the body as a form of penance, and his example was followed by the locals. Gatherings became more organized, albeit painful.

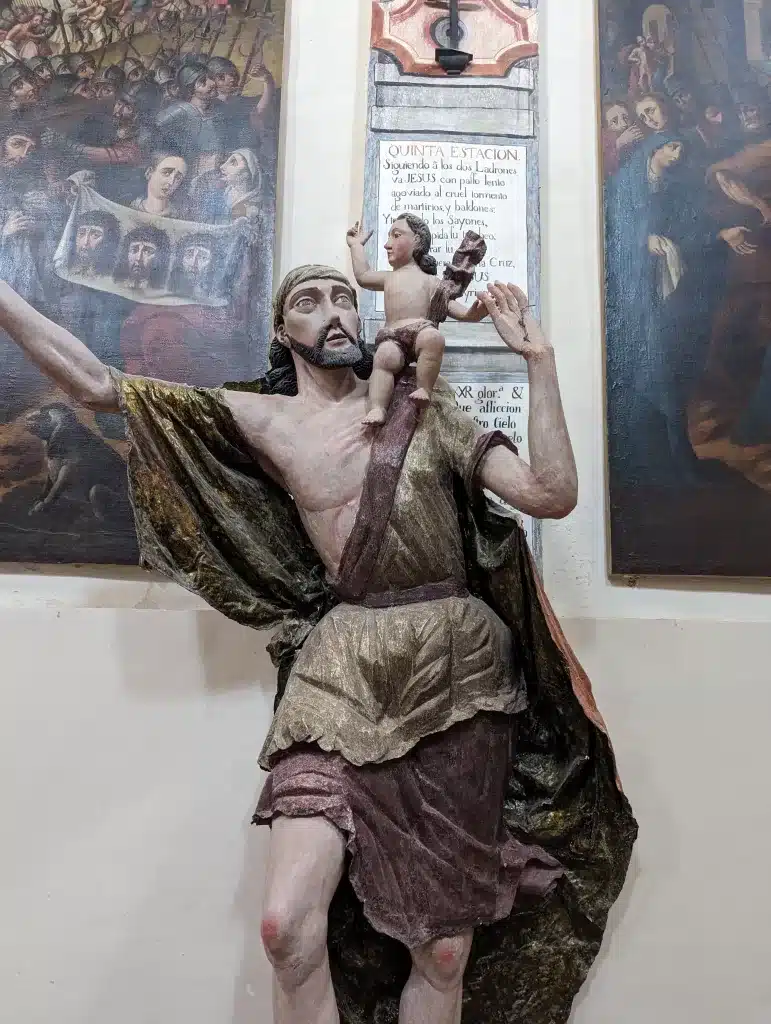

He also commissioned an untrained “artist of the people,” Antonio Pocasangra, to cover the entire interior of the church with mural paintings. In addition to the anonymously created wood sculptures in the various chapels, the church serves as a repository for religious Mexican folk art.

V. The Sanctuary

Today Mexican muralism is acknowledged as some of the most important “public art” in history. This is due mostly to the great 20th-century mural movement of the “big three”: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Their work, dealing in secular subject matters like political revolution and worker empowerment was a modern phenomenon. Since the establishment of New Spain in the sixteenth century nearly all the artwork in Mexico had been dedicated and paid for by the church. However, muralism in Mexico can be traced to the very beginnings of Mesoamerican civilization. Far more than “cave paintings”, the Olmecs created detailed wall depictions representing everything from their mythological deities to images of everyday sports.

The Mayans were prolific muralists and murals can be found in hundreds of ruins. The ancient Mayan city of Bonampak is best known for the colorful floor-to-ceiling murals that cover the interior walls of its central acropolis. Bonampak is located up a tributary of the Usumacinta River in what is now eastern Chiapas, Mexico. The site’s engraved and sculpted stelae (upright stones) and its beautiful murals document the ritual life, war practices, and political dynamics of the Late Classic Period of Mesoamerican civilization.

The Murals of New Spain

We don’t know exactly the works that inspired Alfaro to commission the painting of every surface of the Sanctuary of Atotonilco but he likely spent a great deal of time in Mexico City’s great cathedrals during his young life as a son of nobels.

It is likely he was exposed to the work of Rafael Ximeno y Planes, who covered the dome of the Catedral Metropolitana de Ciudad de México with frescoes as well as the walls of the Jesús María and La Profesa, both in Mexico City, where Alfaro grew up.

Choosing an unknown, Mexican-born local was an unconventional yet inspired choice. Antonio Martínez de Pocasangre was contracted to spend what amounted to 30 years of his life to illustrate in full detail, the life of Jesus Christ.

The complex is richly decorated floor to ceiling in hundreds of paintings depicting the life of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, interspersed with bloody life-sized carvings and the mystic verses of Father Alfaro himself. Pocasangre’s murals begin immediately, encircling the church doors just inside the vestibule. His scenes of men being strangled by snakes and eaten by demons carry the great weight of conviction. Behind them, in verse, Father Alfaro spells out the punishments of sin:

This mouth, which threatens you horribly,

savagely and voraciously

even if it eats more and more,

it is never satisfied:

It takes advantage of your fear,

because if it could

it would submerge the whole world

and bury everyone in Heaven.

Fun stuff. I was overwhelmed by the detailed gorgeous frescoes, especially the deep blues of the background that juxtapose the foregrounded maroons of flesh of blood. The violence displays Father Alfaro’s interpretation of the wages of sin. His influence is not just clear but foundational, within dozens of the most visible murals are his theological poetry, translations, and interpretations, some, like the one above, are translatable via my phone’s app, some of which are not due to extreme fading.

Originally built to use the thermal hot springs with pools and plumbing providing easy access to these sacred waters, not surprisingly, in the centuries following the completion of the Sanctuary, the murals were subject to deterioration due to the resulting humidity.

In 1994, the World Monuments Fund named the Sanctuary of Atotonilco one of the world’s 100 Most Endangered Monuments. This inspired a major restoration project that same year. The church was in good hands: some of the team that had worked to restore the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican City helped breathe new life into these frescoes. In addition, the walls were cleaned, the foundation was reinforced and a new drainage system was installed, diverting the thermal springs away from the Sanctuary completely.

In one glass case, I found El Senor De In Columne, the main figure to be carried on the all-night march from Atotonilco, leaning on a short column, hunched over, and exhausted. He had long red stripes on his scalp from the lash, and his narrow Spanish face was a mask of suffering and serenity.

In one glass case, I found El Senor De In Columne, the main figure to be carried on the all-night march from Atotonilco, leaning on a short column, hunched over, and exhausted. He had long red stripes on his scalp from the lash, and his narrow Spanish face was a mask of suffering and serenity.

Capilla de Calvario

“It is important to emphasize that the priest of the Sanctuary exaggerated the public display of his virtues while emphasizing the penitences and severe punishments that were included in the spiritual exercises.” (Marquez)

To the left of the main entrance are the doors to the most stunning wing of the structure, the Capilla de Calvario (Calvary Chapel). It is the largest structure in the complex, constructed between 1763 and 1766. It is also the final work of Father Alfaro, though he did not survive to see its interior complete. The chapel is designed with a cross-shaped layout and is completed with a cupola, vaults, and columns. The decoration of the chapel is largely Spanish Baroque in style, featuring monumental oil paintings (which differ from the tempuras of the main vestibule), as well as groups of painted wood sculptures that are hung from the ceiling, floor, and walls.

The columns are inscribed with poems written by Alfaro, and the three altars feature wood sculptures in the central transept of the chapel. These sculptures portray the Crucifixion, the Agony, and the Descent of Christ from the cross.

The primary purpose of the religious art displayed in the Sanctuary was to encourage the faithful who attended his retreats to feel the presence of the Holy Spirit, in accordance with the principles of Catholic Reform of the time. As a result, the numerous pictorial works displayed in the Sanctuary served as a powerful encouragement for those who had converted, as well as for those who had already accepted the Eucharistic union and the mystical experience that the Neri movement pushed.

VI. The Procession of Ignatius of Loyola

We are visiting in the days leading up to tomorrow’s Passion Sunday, two Sundays before Easter when a massive procession unfolds from within the heart of Atotonilco. At midnight tonight begins a profound demonstration of communal faith. Approximately 20,000 pilgrims join in a 20-mile walking procession from the Sanctuary of Atotonilco to the Church of San Juang de Dios in San Miguel de Allende. Each year, they gather in the plaza around 11:30 pm, awaiting the sacred ‘Imagenes’ to emerge from the church.

As we exit the church and head to a reputable guisado stall with the most fantastic handmade blue corn tortillas, cars are parking and people are gathering. The procession commences at midnight and continues until dawn, the group carries a life-size representation of the Virgin Mary and the bleeding Christ over the rugged terrain. Passion Sunday would be our last morning in San Miguel de Allende and we made sure to be there for the conclusion of this procession early the next morning.

This ceremony was started by Father Alfaro and many of the rituals of the modern procession are based on his actions and teachings. During the week, the village is relatively quiet, and visitors are likely to be the only ones in the area. However, tonight, the town is filled with pilgrims who are seeking penance and penitence. These pilgrims purchase a variety of items, such as rosaries and crucifixes, as well as sackcloth clothing. Additionally, they purchase ropes and whips, crowns of thorns, and wooden stools with three legs. Many of the marchers place the thorned coronas upon their heads and clasp them in a state of penance, drawing blood, others carry bottles of holy water to aid in their journey. This arduous exercise of devotion is rooted in the intense inquisition era traditions of physical penance Father Alfaro was obsessed with.

The crowd waits until the figures of Sr. de la Columna, the Virgin of Dolores, and San Juan are reverently removed from their places within the sanctuary. Adorned with silk scarves and carefully covered, they are prepared for a sacred journey – an all-night pilgrimage to San Miguel in anticipation of the upcoming Semana Santa celebrations and processions.

As night falls, the air reverberates with the dense chimes of the antique tower bells. Banners sway gently in the night, and hundreds of luminarias cast a soft glow on the faces of the crowd. Then, the moment arrives. The three Imagenes, cradled on wooden platforms, are brought forth from the church. A short mass is broadcast over a loudspeaker, marking the beginning of the procession.

The route winds its way through El Cotijo, leading to a chapel just off the highway where a 3am mass is held. From there, it proceeds to a small village, its entrance adorned with a carpet of flowers framed by arches of palm fronds.

Elderly men and women, supported by family members, walk alongside babies cradled in arms and pushed in strollers. Teenagers and adults join the procession, while groups of men in white hats lead songs. Notably, some of the devoted undertake the entire eight-hour journey barefoot, demonstrating their commitment to penance as taught by Father Alfaro.

Early in the morning, just after dawn, we watch as the procession arrives in San Miguel to the cracking of fireworks tearing through a quiet morning sky. While we are exhausted from having to get up a little early, the pilgrims themselves are overflowing with energy, smiles on their faces, and tears of joy in their eyes. The ecstatic energy of the ritual is moving, palpable, and undeniable.

Beyond my comprehension, my interests, and my boundaries, Father Alfaro’s interpretation of the Ritual of Ignatius of Loyola has traveled 20 miles and 250 years to be here this morning. His Sancturay still stands and to be within its walls is powerful for believers and non-believers alike.

I may be wrong but what I see is a testament to the power of art. I wonder if Father Alfaro’s bizarre penance rituals would still be practiced today if not for the incredible talent and dedication of Antonio Martínez de Pocasangre. By fulfilling Alfaro’s vision and venerating his work through Pocasangre’s paintings, Alfaro was able to move people to seek penance and patience centuries after Jesus appeared to him and instructed him to build the Sanctuary.